All images © Robin Goldsmith, unless otherwise indicated

Firriato Winery's Etna estate, Cavanera Etnea, watched over by the volcano: image provided by Assovini Sicilia

About 20 years ago, I paid my first visit to the jewel of the Mediterranean that is Sicily. A photographer's paradise, even for those who only use a mobile phone for happy snapping, architecturally it's a stunning and fascinating place with a rich history. For visiting food lovers, it's also a haven, with basic staples of fruit and vegetables, as well as the local fish, seafood, pasta and risotto classics, a far cry from what we're used to in UK supermarket aisles … and not forgetting that well known four-scoops-of-gelato-a-day diet! "Have you seen the size of those lemons?", "Have your cheeks exploded with the sheer juiciness of these giant peaches?", you may well cry out. Yet it's the wine that will always leave a lasting memory. It was in a Sicilian wine bar in Taormina that I had my first taste of Donnafugata Mille e una Notte … and I was hooked!

Returning to the UK with two bottles of Etna wine - a Bianco, unfortunately oxidised when I opened it before a dinner party, and a Rosso, perfect with the evening's salmon as light and slightly off-dry - I was convinced that Sicilian wine had a global future. Fast forward 20 years and the wines have changed - both in style and quality. While, as I found out all those years ago, the island's wines were not considered suitable material for a dedicated tasting event in the UK (I did ask!), nowadays that is certainly not the case. This was brought into focus even further by my second trip to Sicily in May this year.

Sicily is the largest island in the Mediterranean, covering around 25,000km2. It has a rich wine heritage dating back 2,600 years, blessed with excellent conditions for grape growing despite its location in the potentially heat-ravaged southern reaches of Europe, 96 miles north of Tunisia. Indeed, the ancient Greeks recognised how great Sicily was for viticulture, giving the island the nickname of Oenotria.

Yet, at the same time, Sicily has been a bulk wine region, making wine for the rest of Italy, particularly the north. It's only relatively recently that its quality credentials have been recognised globally and this is largely due to the establishment of Sicilia DOC in 2011.

Sicily has nearly 100,000 hectares of vineyards, although pre-phylloxera, the vineyard area was three times larger than it is today. There are 26,000ha certified organic (28% of Italy's organic vineyard surface area), more than in any other wine region in the country. Sicily on its own represents 8% of the world's organic vineyard surface area, the third biggest region worldwide.

Sustainability is a core value of the Sicilian wine scene and 42,000ha are managed sustainably without the use of herbicides and synthetic fertilisers. The island was the first Italian wine region to introduce a sustainability code with ten minimal requirements, covering vineyard management, biodiversity, energy efficiency, bottle weight and more.

Organic farming at carbon-neutral Firriato Winery: image provided by Assovini Sicilia

There is currently one DOCG, Cerasuolo di Vittoria DOCG, and there are 23 DOCs, including the island-wide Sicilia DOC, covering white, red, rosé, sparkling and dessert wines. Unlike the individual denominations, Sicilia DOC allows varietal labelling if made from at least 85% of the indicated grape variety. The remaining 15% must come from specific authorised varieties.

Investment and forward-thinking have helped propel the Sicilian wine industry on to the international stage, as well as improve the quality of its wines. Mazzei, Zonin, Gaja, Gruppo Italiano Vini (GIV) and others have all made their mark, while Planeta, Donnafugata and Tasca d'Almerita were the first to plant international grape varieties back in the 1980s. Indeed, Planeta's Chardonnay launched in 1995 was the first barrel-influenced Sicilian Chardonnay on the international market.

Sicilia DOC allows for 14 indigenous and 13 international grapes. Some native grapes have been rescued from near extinction and young winemakers are spearheading the revival of these 'relic grapes'.

Nero d'Avola and Grillo are the most widely planted red and white grapes, respectively. Wines from both are increasingly finding their way into the UK, along with other Sicilian-grown varieties, highlighting the modern consumer's desire for vibrantly fresh, fruity, interesting and often saline expressions.

Nero d'Avola represents 16% of grapes grown in Sicily. It produces a variety of styles from light, almost Pinot-like expressions, to the more familiar plum, chocolate and pepper notes, similar to Syrah. If planted on sandier soils, floral and spicy notes develop, whereas clay soils tend to give more bitterness and acidity.

A bush vine of Nero d'Avola: image provided by Assovini Sicilia

Grillo, created in 1873, is a crossing of Catarratto and Zibibbo (Muscat of Alexandria). Meaning 'cricket' in Italian, wines made from the grape can be light with citrus freshness or more textural and weighty.

Catarratto used to be the most widely planted grape in Sicily, particularly on the western side of the island where it's one of the grapes allowed in Marsala. It's now also used for light, refreshing, fruity, floral and citrus-driven white wines with good acidity, although more complex, higher altitude examples exist. It's sometimes combined with Chardonnay, a uniquely Sicilian blend. The grape is also known as Lucido, meaning shiny, a reference to its appearance.

Frappato is a great example of how a red grape can be used to make wines that suit chilling and often pair really well with fish. This Sicilian variety produces light-bodied, aromatic wines with a juicy red fruit character and often a herbal edge. Cerasuolo di Vittoria, the island's only DOCG, is a blend of 50%-70% Nero d'Avola and the rest Frappato.

Perricone is one of the relic grapes rescued by the new generation of winemakers. Although often blended with Nero d'Avola, it's now being increasingly made into aromatic and savoury, single-varietal wines.

The island's Mediterranean location, surrounded by sea with constant winds, gives it a fairly consistent climate with dry, hot summers and mild, rainy winters. Milder near the coast, but hotter and more humid inland, the island has some protection against climate change and drought, despite years of extreme heat, like in 2021. The diurnal range can reach 25°C in the mountains, with sea breezes and high altitude providing a cooling effect, particularly at night. Given its beneficial location, vineyard irrigation is not often needed, but is allowed in emergencies.

Sicily is the second most mountainous area in Italy after Alto Adige. Geography and soils on the island are varied. Over 60% of vineyards are on slopes, while around 24% are located on mountainous land and the remaining 14% lie on flat land, mainly in Catania on the east coast. The highest vineyards are unsurprisingly on Mount Etna, reaching altitudes of up to 1300m above sea level. In addition to lapilli-rich volcanic soil from Etna, clay, sand, limestone, schist, metamorphic rock and chalk soils exist on the island.

As a result of this mixed terroir, Sicily can be divided into five distinct viticultural areas:-

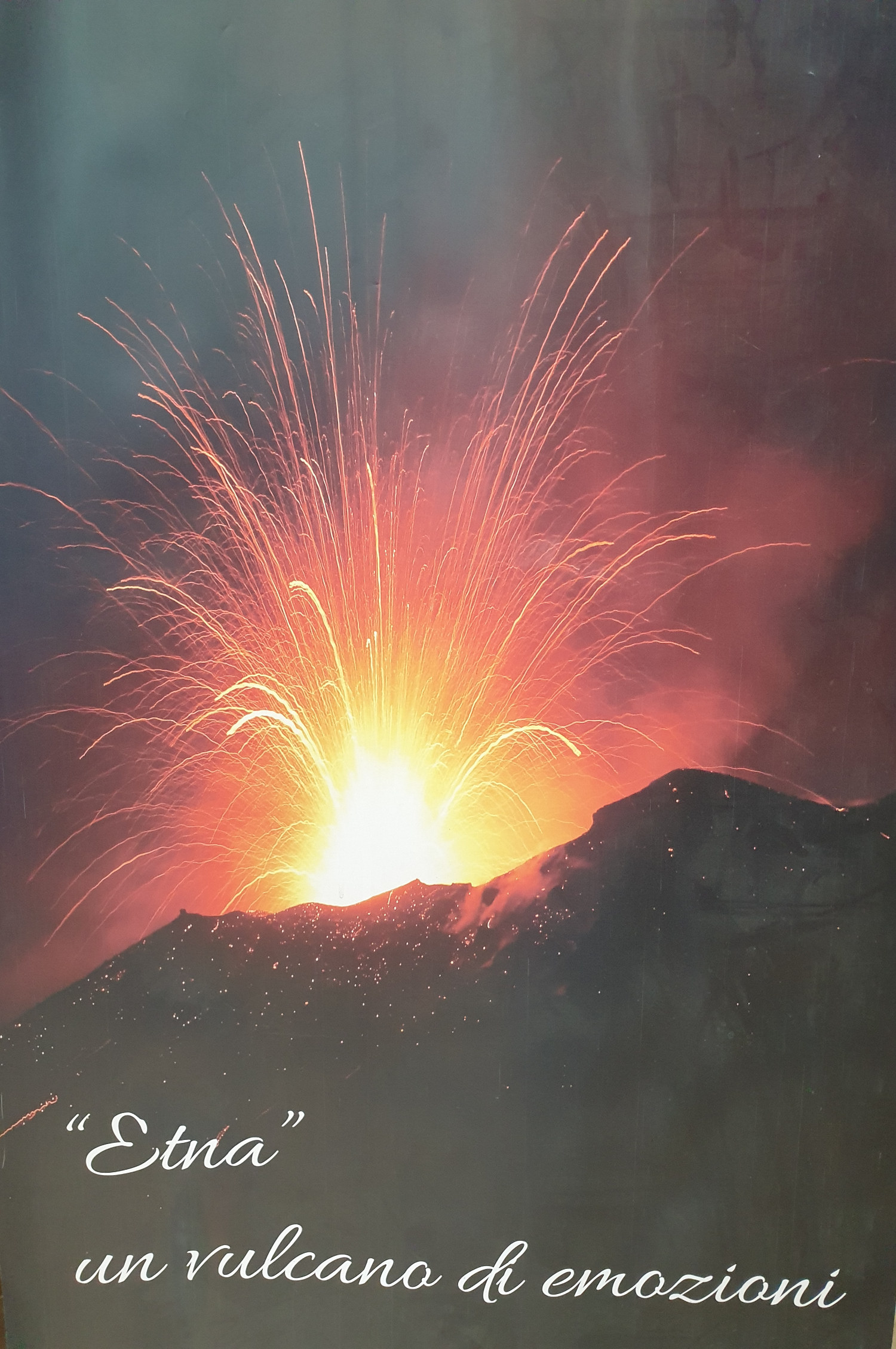

The explosive power of Mount Etna, showing the remains of a hotel following the eruption of 2002

One specific part of Sicily that has seen a huge surge of interest and investment in its wines and vines is Etna. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Mount Etna is a unique, volcanic wine area and home to some of the oldest vineyards in Italy, many pre-phylloxera.

To call a volcano an active volcano, it must have at least one eruption every 10,000 years. In general, Etna has 20-30 per year, making it a hyperactive volcano! 🌋

Formed half a million years ago and located between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates, Mount Etna is the highest active volcano in Europe. It also has a long history of winemaking dating back to ancient Greek civilisation in the eighth century BCE. Phylloxera arrived late due to the prevalence of sand and lava soils and high altitude (some limestone and clay at lower ground, which was more affected by phylloxera when it eventually arrived). This led to a big decrease in vineyards, but the last 20 years has seen a resurgence.

The rebirth of Etna wines began around the turn of the millennium on the north slope of the volcano, notably between the villages of Solicchiata and Passopisciaro in the province of Castiglione di Sicilia. However, the background to this renaissance had already begun to take shape much earlier in 1968. This is when Etna DOC was established, the oldest DOC in Sicily, followed by the formation of the Consortium for the protection of Etna wines in 1994.

Today, there are 1,300ha of vines falling within the denominazione, still a far cry from the 90,000ha around 150 years ago and 40,000ha in the early 1900s, following the arrival of phylloxera.

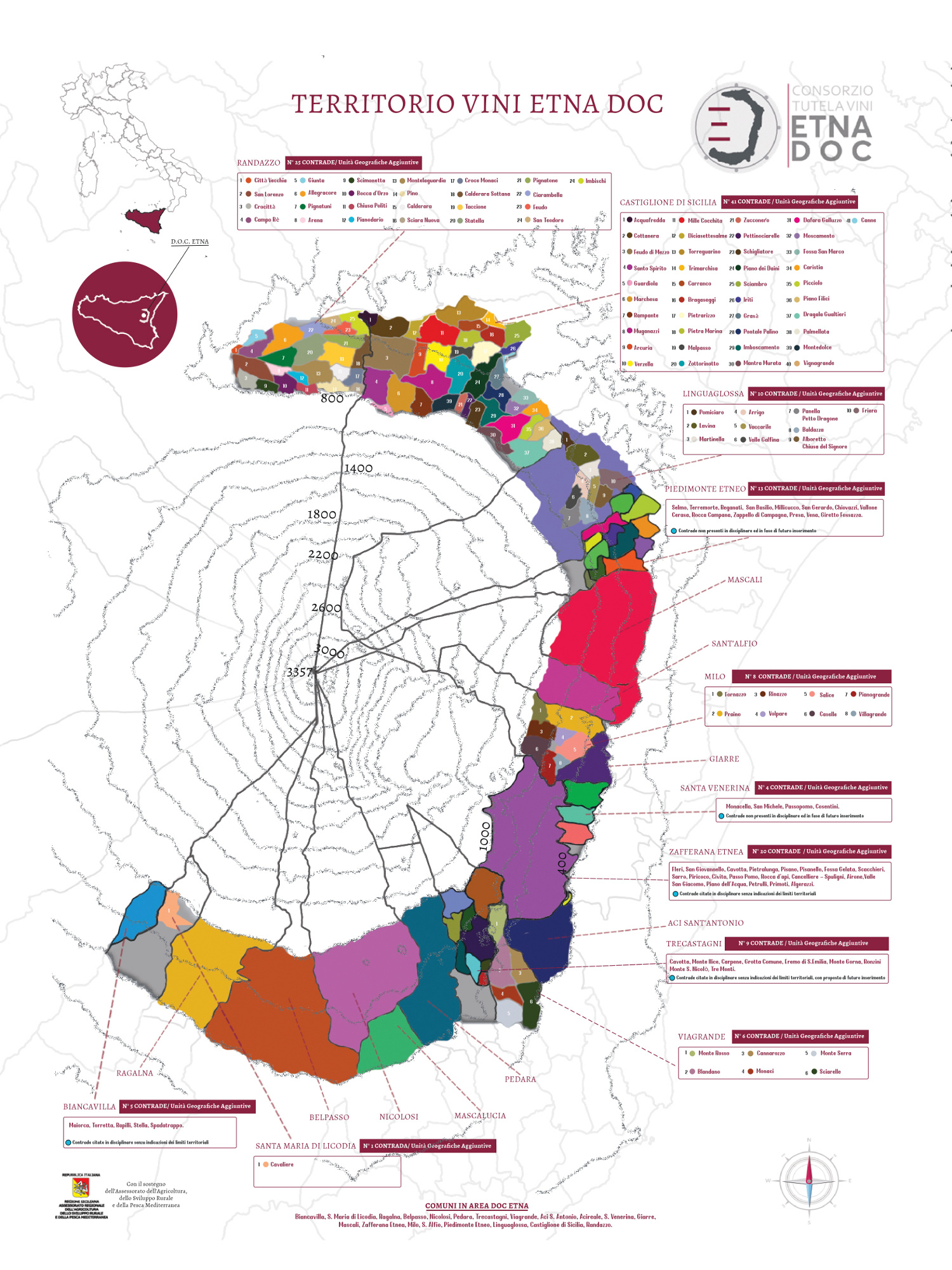

The four vineyard slopes of Mount Etna: © Consorzio per la Tutela dei Vini Etna DOC

Etna's vineyards are located on the northern, eastern, south-eastern and south-western slopes, each bringing their own terroir influences with differing exposures to the sun and distinct layers of lava. The western side is too rocky for vines, but nuts, fruit and vegetables can be grown.

The northern slope is the coldest, has the highest number of producers and the gentlest slopes. The dominant grape is Nerello Mascalese. Although it used to be thought that only red grapes could be grown successfully here, many producers have been achieving excellent results with Carricante and this is likely to continue. Diurnal range is usually 15°-18°C, while annual rainfall is typically around 800mm.

The eastern side, overlooking the Ionian Sea, is the most exposed area to rain (average 1000mm per annum), wind and humidity, making it more suitable for white grapes, particularly Carricante. It is here that Etna DOC Bianco Superiore can be made from grapes grown in Milo.

The south-east also benefits from cooling sea breezes, in contrast to the south-west, which is furthest from the sea, so prone to hot winds, less rain and a greater diurnal range (20°-25°C).

So, with distinct microclimates and maturation cycles, harvest dates differ between the north and south of the volcano by as much as 20 days, the south having the earliest harvest. In 2023, a year beset by extreme weather conditions and resultant downy mildew, Sicily's grape harvest, the longest in Italy, lasted 100 days. Beginning in the western part of the island during the first ten days of August, the harvest finished at the end of October in the vineyards of Etna.

The Contrade on Mount Etna: © Consorzio per la Tutela dei Vini Etna DOC

The slopes of the volcano are richly biodiverse, so the area cannot be seen as a homogenous wine region. Therefore, Etna DOC is divided into contrade across 11 municipalities. In effect, each of these territorial subdivisions represent Etna's own version of a cru, delineated by the different lava flows. Currently there are 142 contrade, having recently increased from 133, all inextricably linked to the volcanic activity that has shaped Etna's unique terroir.

Under the DOC rules, for a wine to be labelled with the name of a contrada, the grapes must come from the specified contrada, like a Burgundian cru. However, while their existence helps winemakers highlight the diversification of Etna's soils, not everyone is convinced that a contrada on Mount Etna can really translate to a cru. "A cru in Burgundy is small, while in comparison, the contrade on Mount Etna are huge", says Michele Faro, owner and founder of Pietradolce on the northern slopes. "That's why inside the different contrade, we've tried to identify some small 'clos'. So, inside Contrade Rampante, we produce three different clos: Barbagalli, Archineri and Rampante. This gives an idea of how different the small terroirs of Mount Etna are."

While each contrada can incorporate DOC and IGT wines, the Etna Wines Consortium sets the DOC rules for maximum vineyard altitude - 800m above sea level for the north and 1000m for the other slopes. This means that some excellent wines made from grapes grown at over 1000 metres, for example on the south-western slopes, should be labelled Terre Siciliane IGT, as they aren't covered by the Etna DOC regulations.

Layers of volcanic soil on Mount Etna: image taken at Graci winery

The lava flows, with differing temperatures and mineral content, have the greatest impact on soil composition and texture and on the type of plants grown. So, soils vary across the contrade, coming from distinct geological era and encompassing different types and densities of basalt and other rocks, black or brown sand, gravel, clay etc. Thus, the lava flows with their particular mineral compositions have formed the soil characteristics of the individual contrade and the wines made in each one have their own qualities too.

"We studied the soil and found five different kinds", says Alberto Graci of pioneering Etna producer, Graci. "The stonier soils are on the top, while at the bottom, there is more sand brought down each year by rain. So vineyards have different soils with different stratifications, levels of sand and stone."

Research is still needed to better understand the soil differences across the contrade. Francesco Cambria, co-owner and founder of Cottanera and President of the Etna Wines Consortium, confirms that this is currently taking place. "We are doing a study to map the soils of Etna. It's not just a map of the contrade, but the soils too, showing the differences from one to the other. I hope this will be ready within the next two or three years."

The 'palmento' of Palmento Costanzo

Organic-certified Palmento Costanzo owns 18ha on the northern slopes of Mount Etna and they also cultivate vineyards in the south-west. The word palmento means millstone and refers to the traditional winery building on Mount Etna, dating back many centuries.

Serena (l) and Valeria Agosta (r)

Valeria Agosta and her daughter, Serena, owner and winemaker respectively of Palmento Costanzo, explain further about the terroir on Mount Etna, highlighting the Santo Spirito vineyard, home to their oldest vines at just under 800m altitude. "There is always lava, sand and rock, but with different textures. In Contrada Santo Spirito, we also have some areas with ghiara soil [reddish aggregate outcrops with silt, gravel, pebble and clay fractions beneath solidified lava flows], close to the 1879 lava flow. It's a more fertile, richer area." They regard this site as their 'Grand Cru' equivalent, with wines showing a distinctive richness along with the characteristic Etna minerality.

Terraced vineyard at Pietradolce

At Pietradolce, terroir differences are similarly key to their range of wines. The Nerello Mascalese grapes grown in vineyard plots, named Archineri and Rampante, on the northern slopes of Mount Etna result in very different wines. Yet these plots are adjacent, both within the same contrada. The parcels are separated by two different lava flows, a natural wall against phylloxera. Archineri is protected by trees with a fresher and windier microclimate and growth is more vigorous. Rampante is warmer with better exposure to sunlight with soil that's less fertile and full of iron and manganese. The resultant Etna Rosso Rampante is powerful and juicy, while the Archineri perhaps shows more finesse and minerality.

Alberto Graci explaining the complex geology of Mount Etna

Alberto Graci also comments on the differences between neighbouring contrade. "Arcurìa is 600m above sea level, while Muganazzi is 750m. You can go in a couple of minutes from one to the other, but there's a big jump of altitude. Two very close contrade in two different positions. We harvest our Carricante 20 days earlier in Muganazzi than in Arcurìa, where it's more humid and the maturation cycle is very slow. Consequently, the wine styles are different, with Muganazzi showing more minerality and Arcurìa a deeper texture."

Carricante is an ancient white grape from Etna, traditionally grown as alberello bush vines (see below), particularly on the eastern slopes of the volcano. The mineral-rich sandy soil and large diurnal range are ideal and the sea-facing vineyards up to 900m altitude allow the grapes to retain freshness, delicate aromas and good levels of acidity. Typical characteristics include citrus and white fruit with defined minerality. There are 410ha of Carricante planted on Mount Etna. It is often blended with the thicker-skinned and more aromatic Catarratto, adding structure and complexity.

Catarratto is another indigenous grape variety. As mentioned earlier, it used to be the most widely planted grape in Sicily, particularly on the western side of the island. Its popularity on the volcano has been declining, where generally it's blended with Carricante, although some fine, single varietal expressions exist. Typical characteristics of the grape include citrus and herb aromas, structure, freshness and minerality.

Nerello Mascalese is the most widespread grape variety on the slopes of Mount Etna and is used for red, rosé and sparkling wines. It's a thick-skinned grape and wines tend to be medium-bodied with relatively high levels of alcohol and acidity, red fruit and floral notes, minerality, good tannins and often a smoky edge. There are 750ha of Nerello Mascalese on the slopes of Mount Etna.

Nerello Cappuccio is used within blends alongside Nerello Mascalese. It has more concentration of anthocyanins, so adds a deeper ruby colour, together with herbaceous and spicy aromas, delicate tannins, freshness, structure and complexity.

Other grapes are also grown, but these are the main four that characterise Etna's unique wine styles.

Alberello vine training at Pietradolce

Both Palmento Costanzo and Pietradolce, like many others on Mount Etna, use a traditional method of viticulture called alberello, particularly for their oldest, ungrafted, pre-phylloxera vines. Rather than planting in rows on steep slopes, terraces were dug out of the lava rocks to make it less difficult to work the land. Basalt deposits from volcanic activity provided the rocks and stones to build dry stone walls that divide different properties and protect against erosion.

Vines are planted 1.1m apart in a quincunx (five point) arrangement and propped up by hard-wearing chestnut posts to allow the shoots to be tied on the tip of each post. "With this type of cultivation" says Valeria Agosta, "[our ancestors] believed that the vines would get more sunlight during the day and also the roots of each plant would compete to go deeper into the soil for water and nutrients." In this way, they managed to maximise plantings on steep slopes and take advantage of the perfect exposure to sunlight throughout the day.

'Propaggine' at Palmento Costanzo

Other ancient techniques may also be used. For example, at Palmento Costanzo, you can also find examples of propaggine or marcottage, a traditional method of propagation in which a vine is tilted into the ground and buried. It eventually emerges a short distance away with at least one bud. After two years, it's cut off from the original vine, so a new plant emerges in its own right.

Today, cordon spur is the most common training system, as it's easier and cheaper to maintain. For example, at Tornatore, who grow vines in different contrade on the northern slopes of Mount Etna, cordon spur-trained vines are spaced 90cm to 1m apart in Contrada Pietradizzo. However, like many on Etna, they keep some alberello to maintain the tradition of their ancestors. Indeed, terraces of alberello bush vines remain a common sight in this part of Sicily and a clear reminder of Etna's long winemaking history.

At Cottanera, they choose particular cordon-spur trained vineyards of Nerello Mascalese for their Etna Rosato and prune in a different way from the vines reserved for Etna Rosso. Yields are higher - 8.5 tonnes per hectare, as opposed to 5.5 to 6.5 tonnes per hectare - and they keep more leaves on the vines to shield the grapes from the sun. As a result, the grapes are fresher with lower alcohol and sugar, good fruit but less concentration and lower phenolics, perfect for the style they want to produce.

Labels of Palmento Costanzo bottles are made from lava powder!

At higher ground, the altitude and wind give protection, meaning that organic and/or sustainable viticulture remain widespread, with copper and sulphur often the only chemical treatments used in the fields.

Vincenzo Bambina, Tornatore's head winemaker praises the suitability of the volcanic terroir for a more natural approach to winemaking. "Etna is a special space and you don't need to do so many things as a winemaker to make a good wine. You should do it in a natural way, otherwise you could make mistakes."

Palmento Costanzo's Valeria Agosta comments further. "It's easy to be organic on Etna due to the wind, which helps in spring when temperatures are higher and humidity can bring mildew. We use copper and sulphur, but no other chemicals."

Winery roof at Pietradolce

Pietradolce is organic certified for viticulture, but not for vinification, concerned more with being sustainable in the fields. They also use only copper and sulphur, encouraging biodiversity with many species of plants and trees, including olives, chestnuts, walnuts and almonds, "creating competition between pests and predators around the vineyards". The rooftop of their winery is similarly landscaped with the typical plants and shrubs found around Mount Etna. Volcanic stone walls and plant life on the roof also reduce the energy costs of cooling the building.

Cottanera is certified sustainable from the field to the bottle, but not organic. "Sustainability is more complete", says Francesco Cambria, "because it starts in the vineyards, incorporates the social side and continues to the bottling. We use sustainable bottles produced in Marsala, so there isn't even much transport involved … and we have lighter bottles as part of the sustainability code."

The 2023 grape harvest in Italy was the least productive since 1947. Similar to all central-southern areas of Italy and southern areas of Europe, Sicily suffered a 31% drop in production compared to 2022, with downy mildew a major feature. Although partially protected by altitude and wind, Etna was not unaffected, particularly in the north and/or at lower altitudes, where many producers lost over 60%, including some in excess of 90%. The south suffered less (around 30-35% loss on average), while the east experienced few problems.

At Maugeri, located in Milo on the rainy and windy, eastern slopes of the volcano, sea breezes help to dry the vines and maintain freshness in the grapes. Export, Sales and Marketing Manager, Gea Calì, notes that since winegrowers in the region are so experienced in handling their particular weather conditions through vineyard management, Milo was barely affected by downy mildew last year.

Producers on Etna are not ignoring the warnings of climate change. Some are looking to plant vines at higher altitude. Others, like Palmento Costanzo, are experimenting by pruning certain parcels a month later, delaying the vegetative cycle of the grapes to control sugar levels. This way, they can achieve physiological ripeness, but delay sugar ripeness. Additionally, they leave plants between the vines to encourage biodiversity and health of the soil.

Climate change and disease pressure were important topics discussed by delegates at this year's Sicilia En Primeur.

Sicilia En Primeur is an international showcase of Sicilian wines. Every year since 2004, the event has been hosted by Assovini Sicilia. This association of Sicilian winemakers, created in 1998, brings together 100 wineries to promote the quality of Sicilian wine around the world.

Mariangela and Francesco Cambria talking at this year's Sicilia En Primeur

Mariangela Cambria, co-owner of Cottanera and president of Assovini Sicilia, echoes the comments from Gea Calì above. "The associated companies of Assovini Sicilia have demonstrated that they know how to manage a challenging situation, such as the last grape harvest, with expertise, know-how and technique. An approach focusing on prevention and prudent and careful management implemented by the producers proved to be successful, as well as a series of agronomic techniques and monitoring activities capable of verifying water stress conditions in advance and being able to intervene promptly."

Francesco Cambria warns that while climate change is bringing forward harvest dates in Sicily and throughout Italy, this has not been seen so much on Etna, protected by its high altitude vineyards. However, he notes that perhaps the diurnal range is slightly lower than it was 15 years ago, which could potentially affect the freshness of wines in the future if this pattern continues.

Some Etna wine highlights at Sicilia En Primeur 2024

There are five DOC categories of wine. However, it is expected that, within the next two years, all Etna DOC production will become DOCG.

Other white grapes: 10% maximum

Other white grapes: 20% maximum

Other varieties: 20% maximum

A proposal has been made to the Etna Wines Consortium to allow Carricante for classic method sparkling wine.

Other varieties: 10% maximum

Other varieties: 10% maximum

While each producer has their own preferred methods of winemaking, many are choosing cement tanks or large wooden barrels to retain the tangy, fruity character and mineral freshness of their wines without overriding wood influences. Additionally, lees ageing adds complexity, while preserving the essential Etna character. In general, entry-level wines are vinified in stainless steel and wood ageing is often reserved for the contrade wines, giving more structure, richness and complexity. Winemakers tend to use indigenous yeasts (can include pied de cuve - a yeast starter culture), but, as Alberto Graci describes, "this is not a dogma".

For Pietradolce's Michele Faro, the method of production should not be the defining character of their wines. "What makes the difference for us is the vineyards - not what we do in the cellar, which is just a way to help, not change the wine. This is our kind of natural way of winemaking - just vinification in stainless steel at entry-level or in tulip-shaped concrete tanks for our pre-phylloxera crus." One exception to this is Sant'Andrea Etna Bianco, Pietradolce's Grand Cru of Carricante from 150-year old pre-phylloxera vineyards. This sees fermentation in 2000 litre oak tanks with eight months on skins, before remaining in bottle for two and a half years prior to release. Despite the long skin contact, this is not an orange wine, retaining excellent freshness, acidity and minerality.

Winemakers on Etna share the desire to maintain the volcanic character of their varieties. For example, Palmento Costanza Etna DOC Bianco di Sei 2022, made from 80-90 year-old vines of 90% Carricante and 10% Catarratto, spends nine months in stainless steel tanks on its lees without malolactic conversion, followed by one year in bottle before release. Serena Agosta explains the reasoning behind this approach. "We stop malolactic conversion with temperature control, as we want to maintain the acidity, sapidity and minerality - typical characteristics of Carricante and the volcanic soil. It's really important to have these in the glass."

Alberto Graci

Alberto Graci, who's also a big advocate for using concrete, has seen significant changes since he began making wine in the region, particularly when the contrade were introduced in 2011. "Everything changed with this approach. It gave Etna an emphasis on the vineyard location, so new producers were focussed on terroir. However, for me, the style of the producer, everywhere in the world, is very important. That makes the difference. When I started to make wine here in 2004, I saw that the majority of producers were using barriques. So, I decided to use big barrels from Piedmont instead. Now I see this everywhere and there is more of a trend to look for elegance. My philosophy of wine is about vibrancy. So even if you can have a very hot vintage, we still go for vibrancy, energy and depth in our wines with great concentration, but also lightness and never heaviness for both reds and whites."

"These are wines of the mountain, full of vibrancy and tension like Etna wine must be", says Alberto Graci.

Graci's approach can be seen in his Etna Rosso expressions, made from 100% Nerello Mascalese, fermented in large, conical wood casks (tini) with long maceration on the skins. The Etna Rosso DOC then spends time in a mix of concrete tanks and 42 hectolitre wooden tini. The result is a ruby-coloured wine that's fresh and juicy with balanced tannins. "We don't do anything to make the tannins softer. It's a wine that comes from an active volcano, so, for me, it must be energetic and authentic."

His Etna Rosato DOC 2023 is very light in colour, made without maceration of the skins after a slow, light pressing. It's fermented and aged in concrete, remaining on its fine lees for eight months. The result is dry, vibrant, mineral and citrussy with a refreshing tang of pink grapefruit. "This is different from other rosatos in Italy", says Graci. "It's not as aromatic and heavy - a wine of the mountain with vibrancy and tension."

A 'tini': a conical vessel for winemaking at Palmento Costanzo

Available in the UK from xtraWine for £39.35 a bottle.

The 2021 vintage is currently available in the UK from xtraWine for £40.20 and Hic! for £45 a bottle.

Available in the UK from VINVM for £20.50 and xtraWine for £28.33 a bottle.

Available in the UK from xtraWine for £83.16 a bottle.

Available in the UK from independent retailers, including Berry Bros. & Rudd for £51 a bottle.

The above wines and others from around Etna pair successfully with many types of food, showing great versatility. At Firriato's Etna estate, Cavanera, a creative food and wine menu brought this clearly into focus. The most imaginative pairing was a red wine and fish combination. Firriato Cavanera Contrada Zucconerò Sciara del Tiglio 2020, made from 90% Nerello Mascalese and 10% Nerello Cappuccio, was an inspired and intriguing choice with olive wood-smoked grouper fish and vegetables in an orange sauce.

The wine shows notes of juicy bramble fruit, plum, dried roses, black pepper, cedar, cloves and tobacco with a hint of liquorice. The wood smoke in the dish mingles effortlessly with the wood influence in the wine that was aged in French oak tonneaux for at least one year. The fruity profile and good acidity of the Nerello grapes match similarly well with the orange sauce. "It's a strong wine for a strong dish", remarks the sommelier.

Sicily is an island with a strong tradition of food and drink and a long history of winemaking. Etna has its own history with distinctive wines that define its unique styles. In effect, it's a wine island within a wine island that feels bigger than it is. "Sicily is not a region, it's a continent!", says Mariangela Cambria. "You don't have time to see Sicily in one go. You have to come back. There are different regions, food and wine all around Sicily."

While the cost of wine around Sicily varies, Etna wines are pricey, as the above recommendations suggest. This does imply that in the UK, they are probably more likely to be available in good restaurants and high-end retailers only. This inevitably means a somewhat limited audience, although a few entry-level examples can occasionally be found in the multiples.

As the popularity of Etna's wines continues to rise, top producers on the island and in mainland Italy are reported to be buying up land and vineyards on Etna. It is therefore no surprise that, as reported last year in the drinks business, the cost of vineyard land on the volcano has increased markedly by up to ten times more than in the rest of Sicily. Does this mean an increase in the average price of these wines? Time will tell.

It would be good to see more Etna wines in the UK market, but high prices and less familiar grape varieties may restrict their appeal. However, harnessing the power of the volcano can help, as many people will be attracted to the strong visual imagery this can provide. Enticing labels can only raise the visibility and further cement the growing reputation of Etna's wines, making them more accessible to a new audience.

The journey up the volcano has begun. Bottle prices (inclusive of an increasingly punitive duty regime) still need to be fair before we see a real explosion on the market, here in the UK. Nevertheless, as Francesco Cambria says, "Etna is a vulcano buono - a good volcano" and the wines made on its slopes are bright and full of energy, benefiting from the volcanic terroir. Concentrated, but not heavy, they represent a style increasingly relevant to the modern consumer. So, perhaps we won't have to wait too long before Etna's gifts are spread more widely for everyone.